How to Optimize Human Reading with Machine Learning (Part I)

How can the reading process be improved?

We spend a lot of time reading to obtain information, thus it is natural to ask how we can augment our reading material, relevant technologies, and other factors of the reading experience so that we may obtain useful information faster, with less effort, and retain the information better.

To approach this problem, it will help to have an understanding of the mental tasks required for reading – something we might obtain by considering how the pseudocode for reading may look. Then like any other algorithm, line by line, we can identify what (and possibly how) aspects of reading can be improved.

NOTE: Of course, we cannot consider every nuance and messiness that comes with human behaviour. A first-order approximation should suffice for our analysis.

1. Establishing Pseudocode

1.1 Seeking Information

For our purposes, reading can be abstractly defined as an act of seeking information through text, under the influence of a set of goals. These goals, whether explicit or implicit as general preferences, differ between people and moments. Examples of simple goals might be to ‘gradually learn enough about what aardvarks eat to write a book on it’, ‘quickly find something which will make for a nice fun fact to tell my coworkers’, or ‘find out how I can extinguish this existential dread’. A goal includes any information about what we wish to obtain information on, how much effort we are willing to expend, and any other preferences or restrictions imposed on the reading process.

Guided by a goal, a first step we take is to locate a set of reading items (the reason for using this specific term, and not ‘books’ or ‘articles’ will become clear soon) from some database (query_database). This can consist of, for example, searching a relevant term on Google to obtain a list of relevant information sources on the results page, or going to a library and locating a set of books. With these reading items, we can then begin to process them (read_item).

def seek_information(goals):

reading_items = query_database()

read_item(reading_items)

NOTE: while goals is only shown as an argument to the seek_information() function, it is an implicit argument in every function call.

1.2 Recursive Processing

Given a set of reading items, we continuously (1) thoroughly study the item in its entirety, (2) locate promising sub-items to process, or (3) stop reading.

NOTE: From here on, to _study something will mean to read something in its entirety, while to read something means to engage in looking for information in that thing._

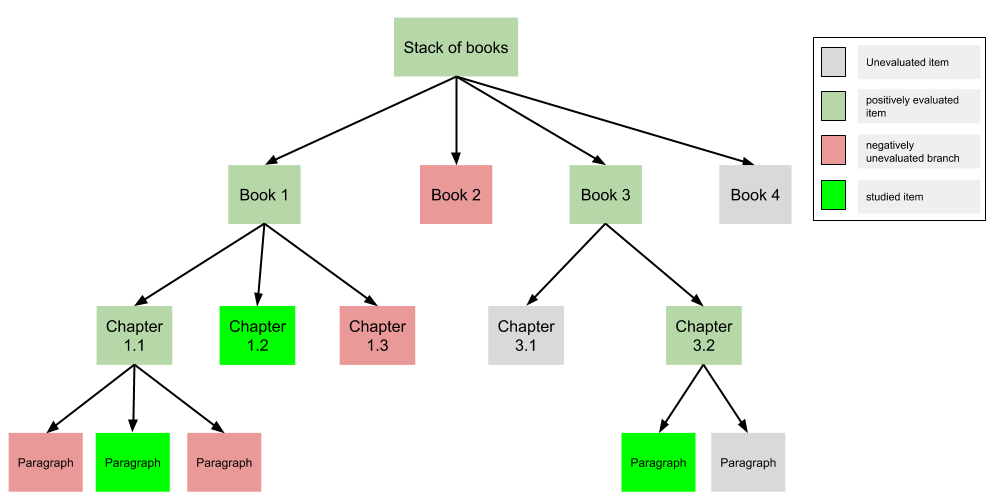

For example, if we have a stack of possibly relevant books, our action sequence at the current level of abstraction might look like: LOCATE a promising book to read → LOCATE a promising chapter in the book → LOCATE a promising paragraph in the chapter → STUDY the paragraph → (fail to) LOCATE another promising paragraph → LOCATE another promising chapter → STUDY the chapter → (fail to) LOCATE another promising chapter → LOCATE another promising book → … → STOP reading (because we met our goal, or got tired, or bored, or distracted, etc.).

From this example, it is clear that a reading item can refer to reading material at any resolution: a stack of books… whose sub-items are books… whose sub-items are chapters… whose sub-items are paragraphs… whose sub-items are sentences… whose sub-items are words. In reality, it can be even more complicated than this, as you might identify multiple groups of promising documents by looking with different search terms, or you might find a document with no chapters, or you might find a textbook which has several levels of subsections, etc.

To emphasize this inherently recursive nature of the reading process, the ‘main loop’ of reading can roughly be described as follows: if the item is small and important enough, study it, otherwise try identify a sub-item to read. In more detail, the pseudocode for read_item might be:

def read_item(item):

study_effort := #estimate effort required to study item

item_value := #estimate value of item

triage_cost := #estimate cost of locating sub-items

triage_savings := #estimate effort saved by locating sub-items

if (study_effort < item_value) and (triage_savings < triage_cost):

study item

return

while item_value > triage_cost:

sub_item := locate_sub_item()

if estimate_value(sub_item) > threshold:

read_item(sub_item)

return

This code makes it clear that before we study an item (or instead choose to break it into sub-items), multiple (often unconscious) cost-benefit calculations are likely made. Guided by the intuition that our brains are designed to be as lazy as they can1, before we expend the energy to study an item, we make sure that it is more energy/effort efficient than possibly studying only a fraction of the item, but paying the up-front costs of having to triage/locate sub-items.

Note that as the goals are met, item values will drop, as they may contain redundant information. Item value is continuously updated to match current goals and progress.

If we decide to triage sub-items, the first step is to locate a sub-item. The locating of sub-items is done primarily visually according to habits, instict, or other mental priors we posess; sub-items to have their value estimated are any reading materials that catches our attention next (which is a largely unconscious process guided by visual salience2).

After a sub-item catches our attention, we estimate its value (discussed next), and if we decide it is important enough, we read it, which starts this whole process over again at a lower level. This function exits the recursive calls once we identify no more items worth reading (either because our goals are met, or we cannot find what we need).

While we may be able to locate books or articles in a library or online, and have a natural ability for locating sub-items, if we are unable to estimate the value of sub-items, we are left aimlessly wandering a sea of text.

1.3 Estimating Value

Without thoroughly studying an item, we cannot expect to perfectly estimate its value with regards to our goals. However, in a gamble to conserve energy, we accept that rough estimates must be made – with faster estimates often being less accurate. Intuitively, the confidence and accuracy of our value estimate of an item is directly influenced by the amount of relevant evidence we can glean about the item. Thus, the process of estimating the value of an item can be summarized: while the value estimate is not confident enough, locate another piece of evidence.

def estimate_value(item):

confidence := 0

confidence_threshold := #minimum value estimate confidence where we are satisfied

effort_expended := 0

effort_threshold := #how much effort we are willing to expend to estimate value

while (confidence < confidence_threshold) and (effort_expended < effort_threshold):

sub_item := locate_sub_item()

item_knowledge := #estimate knowledge contained in item given sub-items so far

# calculate the knowledge value of the sub_item with

# respect to existing relevant knowledge

value := item_knowledge - current_knowledge

confidence := estimate confidence

effort_expended += #effort from locating sub-item and updating knowledge estimate

return value

Now that we have established in some detail the processes we perform when reading, we can consider how such processes can be optimized. Identifying these areas of improvement will be the topic of the next article.